From Industrial Giant to Empty Landscape(And How My Wedding Party Turned into a Riot) |  |

|

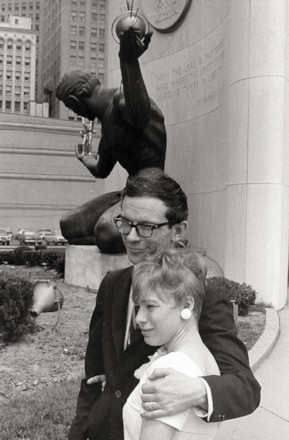

by Theresa Welsh My Roots in FlintI grew up in Flint, Michigan, a classic company town. General Motors ruled, with factory smoke stacks dominating the cityscape and my family's home located in the shadow of the Buick plant where my Dad worked. When I was just a little child, my sister and I used to run to meet my Dad as he walked home from work and fight over who got to carry his lunch pail. There was a lovely little park between where our street ended and the factory property began. In those days, workers often lived near the factory where they worked, and factories were not circled by giant parking lots and security gates as they are now. My Dad worked for Buick for over 40 years before retiring with a pension and health care benefits (He died at age 92 in 2004). The auto industry was good for Flint, and no one would have thought that a day would come when they would NOT build Buicks in Flint, just like no one could imagine that General Motors would one day go bankrupt. Moving to DetroitI attended Catholic schools and graduated in 1963 from St Michael High School in Flint, and could hardly wait to leave this dreary factory town. While growing up, I had loved going to the Big City - Detroit - to see the Detroit Tigers play baseball. My Dad was a huge Tiger fan and so was I. I found the area around the stadium, with its big old houses, fascinating and always wanted to see more of the city. With a scholarship to Wayne State University, I was delighted to leave Flint behind and take up residence in the Big City. Wayne State was just south of the New Center area, so-called because it was like a second downtown, dominated by the huge, ornate General Motors Building and, across West Grand Boulevard from it, the fabulous art deco Fisher Building. These buildings just oozed class and success. General Motors had popular brands of cars with Chevrolet, Buick, Oldsmobile, Pontiac, and that symbol of material success, Cadillac. While there was considerable prosperity during the 1960s, Detroit was not uniformly a place that reflected that prosperity. The city had pockets of poverty and some commercial streets were full of liquor stores, pawn shops, pool halls, wig shops, and various marginal businesses, some of which turned into "blind pigs" at night. A "blind pig" is also known as an "after-hours joint." In plain language, that is a place that sells liquor by the glass after the hours when bars legally have to close. Neighborhoods on the East Side around Kercheval St had plenty of crime, and on the West Side, you had 12th St and Linwood Ave. Detroit was a racially segregated city, with black neighborhoods (mostly the high-crime areas) and white neighborhoods. College and Marriage  David and me on our wedding day in June, At WSU, I met David Welsh at the school newspaper office, where he was a student photographer. In 1967, we got married. We both had apartments on campus, and went looking for a place to share. We answered an ad for a place that the ad said was in the New Center area. However, it turned out to be at the corner of West Chicago and Linwood, a mainly black area. This building was one of two white buildings on Chicago Blvd. It was right across the street from Sacred Heart Seminary, where young men studied to become Catholic priests. We assumed the ad had placed it "in the New Center area" because they wanted to attract white people. The apartment was nice, so we took it. I had watched my family endlessly argue about arrangements and expenses when my sister Barbara got married, so I felt strongly that I wanted none of that. I told David we should just go downtown to City Hall and find a judge, and so we did. I called my mother and told her I was getting married on Saturday downtown and she and Dad could come if they wanted to. Some of our friends came too, and we were lucky enough to get a kindly old judge who seemed delighted to conduct the short ceremony. One of our friends whipped out his wallet and paid the judge, while another produced a bottle of champaigne. The wedding cost us nothing, and I have never regretted doing it this way. 1967: My Wedding Party Was a RiotHowever, my aunts and uncles back in Flint took offense at being deprived of a drunken party (like they'd had for my sister's wedding) and I got feedback that we should invite the relatives to our new apartment to make up for the lack of invitations to a "real" wedding. I made plans to have a buffet spread and a large sheet cake set up in the apartment, and I sent out invitations to my Flint family. The day for this gathering was Sunday, July 23, 1967. If you look up that date in Detroit history, you will find it was the day the 1967 riot began. And, yes, the riot began less than a mile from our apartment on West Chicago. We were not aware of anything as my aunts, uncles and cousins filed into our apartment, which was on the first floor, down a short hall from the small lobby. Most brought us gifts, and we talked and laughed and ate and finally people began leaving. A few had mentioned that there seemed to be some disturbance on nearby streets which they had seen as they drove to our place. Once the relatives were gone, we became aware of noise and strange goings-on outside. We turned on our TV and discovered there was a serious disturbance centered on 12th street that was spilling over into nearby streets and threatening to engulf the West Side. This was not far from where we were now standing in our apartment, listening to the TV and, more to the point, hearing the actual sounds of the riot outside. We began talking with other residents of the building who were now congregating in the hallways. They were very worried because they felt it was the black people who were rioting and we were a little island (two buildings) of white people on a long block of solid black apartment buildings. If it was a race riot, wouldn't we be targeted? I looked at the remains of the buffet table and the pile of gifts on the floor. What would happen to us? Had my relatives made it safely to the expressway? As we talked further with other residents, some went down in the basement to see if there might be anything useful for barricading ourselves or hiding. Some of the residents were pretty racist and wanted to join the fight against the rioters. The manager of this building was a raging racist who used to refer to blacks as "jigs." It seemed odd that he would be living in a building surrounded by black people when he seemed to dislike them so much. A White Girl in a Black NeighborhoodWe, on the other hand, had experienced no problems with our neighbors in the area, and had frequently patronized the gas station on the corner of Linwood and Chicago for repairs to the badly-worn tires on our old car. The owner was a very fine black man named Leon Moon who would cheerfully add another patch to one of our tires when we suffered a flat. At times, the neighborhood did feel a bit alien though. If I was downtown, I would always take the Dexter bus, which involved a longer walk when getting off the bus, back to the apartment rather than the Linwood bus because I knew I would be the only white person on the Linwood bus and that made me feel uncomfortable. It was not that I feared actual danger from these black Detroiters, but rather that I would be the object of curiosity. What was a white girl doing in this all-black neighborhood? Sometimes I wasn't sure and I didn't want to face the question. The Dexter bus went up into a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, so there were usually at least a few other white people on the bus besides me. I had not felt any hostility from any of our nearby black neighbors, but certainly our apartment manager was not kindly disposed toward them and no doubt some of them knew it. I was used to segregated housing patterns from living on campus at WSU, where the white students lived on the west side of Woodward Avenue and the black students lived on the east side of Woodward. But here we were, facing a sea of black people who were rioting in the streets. Not a good situation on this fateful day in 1967 as we contemplated the growing distubances outside. Inside our building, someone suggested going up on the roof for a better look at the extent of the rioting. I liked this idea and joined a few other people and located a stairway to the roof. When we got up there, I looked around in shock and disbelief. In every direction, there were fires. The city was burning. Some of the fires were close, and it was clear this would present a very large challenge to the city Fire Department. I stood there in a daze, wondering if we would all burn up. I will never forget the sight of the city of Detroit on fire. Our cars were parked in a lot right next to the building. One of the men on the roof posed the question: what should we do if the rioters start messing with our cars? David quickly told him, "let them mess with the cars." It was clear that there was little we could do if the rioters decided to target us. I thought about random things like the fact that some of David's pants were in the nearby "40 Minute Cleaners," a building we would later find was a charred ruin. I was sorry my relatives had spent money on gifts, which might be destroyed before the day was over if the fires reached us. I wondered if I'd be able to go to work on Monday or even be alive on Monday. As it turned out, it was days before I would go to work. No one went to work in Detroit during those first days of the riot when the city was engulfed in turmoil. Living Through the RiotFrom our apartment, we could hear gunshot sounds from every direction, and the National Guard rolled down Chicago Blvd in tanks, which they parked at a school just around the block on Linwood. Our bedroom faced an alley, and I was too afraid to sleep in the bed for fear of being shot through the windows. We could see looted items in piles in the alley and hear the looters laughing. We could hear the loud bang-bang of gunshots coming from back there. We slept (or tried to sleep) on the living room floor, which was the furthest spot from a window. When we finally ventured out, we found no one paying us any attention. There were many businesses in the commercial buildings on Linwood, and we found the Middle Eastern family who owned the little grocery store on Linwood sitting inside, holding rifles and looking out the window, challenging anyone to break into their store. The sight of those big guns had apparently kept their store from being ransacked, which had been the fate of many of the commercial storefronts. Up and down Linwood, stores and apartment buildings had placed signs that read "Soul Brother." This was to indicate it was black-owned. Sometimes this seemed to work, but mostly the rioters didn't care. They were having too much fun looting every place they could.

There were certainly racial overtones to this horrendous event, but from our vantage point, it was not a "race riot" since our black neighbors never did turn on us and no one messed with our cars. It did not appear that blacks wanted to hurt whites, but rather many wanted to vent frustrations and, once the riot was underway, get some loot. Their anger was directed mainly at the police and their own economic disenfranchisement. Black unemployment was high, and white people dominated city government and the police department. Black people called this the "white power structure." It was a structure the riot began to dismantle. How and Why it BeganThe riot had begun in the early hours of Sunday as the police raided a blind pig on 12th street. The Detroit police at that time were mainly white, and members of the black community were too often victims of unfair treatment and brutality by the police. On this fateful day, their anger just spilled out and they did not go quietly to the paddy wagons. The riot spread gradually until the late afternoon, when my relatives were all driving back home (they all got out safely), it had engulfed a large part of the West Side. It continued to spread throughout the city that day and the days that followed.

After the RiotIn so many ways, the city has never recovered from the 1967 riot. The main commercial thoroughfares - Woodward Avenue, Grand River Avenue and Gratiot Avenue - were burned and looted and the gaping, empty storefronts remained fixtures for many years. Eventually, some were rebuilt and some torn down and replaced with new buildings, but even more just became empty lots. New commercial residents were few. Detroit became a city without grocery stores, where abandoned stores turned into little storefront churches where itinerant preachers set up shop or became liquor stores where big sheets of plexiglass separated clerk from customer. See my photos and commentary from a visit to the same area, "Revisiting the Site of the Riot", more than 40 years after the event. We moved from our Chicago Blvd apartment soon after the riot to what has to be the worst place we ever lived, an upper flat in the area of 7 Mile and Woodward, an area known as "Chaldean Town" which gradually has become one of the most abandoned parts of the city. We lived in an older two-story wood frame home that had been converted into a two-family dwelling — badly converted. The upstairs had a crazy layout, the landlord was wierd, and the street was full of noisy kids. We didn't stay there long, moving instead to Royal Oak (a northern suburb) where David had a job.

I had always loved the city though and, when David lost his job at the Royal Oak Daily Tribune, we moved to an old building in the Delray section of Detroit owned by a friend who was a free-lance photographer. Since David was taking up the same profession, we shared the darkroom located on the first floor, which had once been a storefront, the windows boarded over so it could become a darkroom. This was an old Hungarian neighborhood which was in serious decline. Located in the southwest part of the city on the waterfront, it was home to Peerless Cement and the Wayne Soap Company. The cement company showered the neighborhood with white stuff that wasn't snow and the soap company contributed a constant sickening smell. Not a nice place to take a walk, but the bar up the street had ten cent beer. We lived in an apartment upstairs over the former storefront turned darkroom. The neighbors were not necessarily friendly. For photos of this area and the building were we lived (later abandoned, but now demolished), see "Abandoned Neighborhoods". See my other Detroit essays too — Descriptions and links here Buying a House At Last — But Not With a MortgageWe eventually moved from Delray back to the suburbs, but I missed the city. We became homeowners in an older neighborhood in southwest Detroit consisting of mostly small houses built close together. We had been unable to get a mortgage because we were self-employed, so we bought into an area where mortgage companies wouldn't make loans. That meant buying on a land contract, with no banks involved. During this time, factory workers could get mortgages right away, since their employment was considered secure and they earned very good money, but people who worked as writers/photographers were not considered reliable. We ended up in a slightly better part of southwest Detroit from where we'd lived in Delray. The area around Vernor and Springwells had a healthy commercial section and mostly well-kept older homes that were close together, with alleys in the back. Our house was a well-built two-bedroom home, on one floor, with a walk-up attic. It had nice woodwork and hardwood floors, a kitchen that lacked modern appliances and one bathroom, with an old clawfoot tub. I was delighted to own a home of my own at last, and I liked the funky neighborhood, but it was not a classy area. The house on the right was occupied by a single father and his sons who were all members of a motorcycle gang. On the other side, was a family whose son was later convicted of being a habitual criminal. Detroit was mostly ignored by mortgage companies, and prices for houses continually fell. We bought our modest house for $10,000 and paid it all off in seven years. Our neighborhood was mainly white and Hispanic people and today is a nearly solid Hispanic area. Yes, white people left the city in large numbers (although I hate the use of the word "flee" to describe this process), but blacks also left as the years rolled by. So, eventually, did we. We were living in the southwest Detroit neighborhood when our daughter was born in 1985 (by this time, we had been married for 17 years and had given up on having children!). Becoming parents took us by surprise, but it was the most wonderful surprise of my life. I was worried about sending our little girl to the nearby public school, and had no better opinion of the Catholic school at the end of our street. When our daughter was three years old, we moved to Ferndale, an older suburb just north of Eight Mile Road (the boundary between Detroit and its Oakland County suburbs). This house was in distressed condition and needed a lot of work; it had been rented out for 10 years. But there was a beautiful elementary school, with a well-kept playground and park behind it, only a block away. We've lived in Ferndale ever since, but now live on the west side of Woodward Avenue in a neighborhood I love. Our daughter Amy has grown up and left Michigan for New York City. For many of us long-time Detroiters, our sons and daughters are leaving for places with better job prospects. Michigan struggles to replace all those good-paying jobs in the auto industry. Detroit's First Black Mayor: Coleman A. Young

I've recently read the autobiography of Detroit's first black mayor, Coleman Young, who presided over the city for 20 years (1973 to 1993). He had grown up in a section of Detroit called Black Bottom (named for the black soil there, not the color of its residents) at a time when people were still coming to Detroit for the good jobs in the booming auto industry. Black people were often doubled up in the only housing they could get which was in the near East Side, an area known as Paradise Valley, that was later "urban renewed" into highrise apartments, and the bustling nightlife of Hastings Street with its famous jazz clubs was replaced with the Chrysler Freeway. Blacks then moved to the area of 12th Street and Linwood, the vicinity of our first apartment on West Chicago. Mayor Young himself lived in the area and says in his autobiography: "One stretch of a steet called Blaine, near Twelfth, became home to more people than any other block in America. Within a few years, the entire Twelfth Street community was one of the most densely populated areas in the country." NOTE: Read my review of The Autobiography of Coleman Young. Looking BackHere's me and David in 2014, at the Packard plant. Now that I'm getting old and have finally retired from a five-day-a-week job, I've initiated a project to go back into the city and see places where I've lived and worked and see what's happened to the city. It's been a shocking discovery. The city has been losing its people and the landscape is becoming empty. Streets that had houses where people lived and loved are now just vacant lots and abandoned buildings, with roofs caved in and trash piled on broken porches. Sidewalks are disappearing as weeds poke through cracks and take over the pavement. Commercial buildings stand empty, with gaping storefronts filled with trash and debris and stairways up to nowhere. Where have all the people gone? Sadly, this is happening all over Detroit. We have taken a number of touring, picture-taking trips throughout the city and have found large tracts of empty land in all parts of the city. Our old apartment building on West Chicago is gone, replaced by an empty field. There are only a few of the former buildings remaining, and up and down 12th street, where the riot began, are abandoned storefronts and empty lots, some now used for urban farming. The East Side has been particularly hard hit, with all of its formerly commercial thoroughfares reduced to weed-filled lots. In some places, whole neighborhoods are gone, and sometimes the streets have been closed off with concrete slabs so cars cannot enter what used to be streets full of houses. The amount of just plain emptiness is shocking and hard to describe in words alone, or even to capture in pictures. This is abandonment. Most of the empty houses stand wide open. You can walk right in the front door and see piles of stuff: broken pieces of furniture, dishes, clothes, etc. Did someone just walk out and leave their life behind? How does this abandonment happen?

The picture at the top of this page is the view from the empty Fisher Body plant on Piquette Street in the New Center area, looking across a field full of trash at another former factory across the Chrysler Freeway. This is an area with many buildings that were once factories, part of Detroit's industrial past. The "GASM" grafitti on the billboard is found all over the city, apparently the work of a busy grafitti artist who isn't afraid of heights. All photos copyright © 2015 by Theresa Welsh and David Welsh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By Theresa Welsh It's July, 1967 and my wedding party was a riot. And How a Once-Bustling Neighborhood Turned into Empty Countryside thousands of abandoned homes throughout the city Abandoned Packard Plant Abandoned Fisher Body Plant Detroit Discards Become Unique Urban Art

BOOKS ABOUT DETROIT

|

Detroit's Spectacular Ruin:

The Packard Motor Car Company built luxury vehicles that set the standard for excellence in styling and engineering in the early 20th century. The huge complex of Albert Kahn-designed buildings was a fixture on East Grand Boulevard, employing as many as 40,000 workers. Its 3.5 million square feet inside the city of Detroit encompasses numerous structures. Packard cars were built here until 1956 when the site was repurposed, but it gradually became vacant, the beginning of a new life as an iconic and most-visited urban ruin. eBook for Kindle and Other eReaders Only $6.95 BUY FROM: |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

BOOKS ABOUT DETROIT Click on a book image below to go to amazon.com for more information. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Seeker Books Home Page More Detroit photos at